Why We Need to Think Beyond Science to Save the World

The Irrational world

Science has its limitations.

We have previously discussed some of these limitations in terms of the perception of truth here. We also talked about how and why it is still worth pursuing truth as it means to us, and also the basic foundational concepts underlying such a pursuit of the truth.

However, the limitations of science don’t end there.

But why should we care? Doesn’t science work well enough to use it?

The problem here is that the point of science is to understand the world around us, and if the tool itself has inherent limitations then the conclusions that could be made from science are always going to be limited.

The argument made here is not that science merely takes a long time or that science often corrects itself with the passage of time. Both of these are understandable, and is what makes science so powerful in the first place.

The real problem is about how science assumed something about the world, which it is wrong about — which is that the world is rational.

When the world is viewed as rational, it limits us significantly, because some things will never make sense under that framework — no matter how much science tries or how much time has passed.

Our rational brain is like a hammer that is looking for nails, but there are no actual nails. Just because we wait a long time or try our very best, doesn’t mean that nails would randomly start appearing. Instead, we need to change our perception of the world so that we no longer think like a hammer.

Before anything changes, we need to first make a case that shows that a rational brain is unable and insufficient to understand the world as it is, because at first glance, it seems we can ignore the irrational and that the irrational is simply that which has not yet been rationalized.

Birth of Rationality

To understand the limitations of rationality, we have to go back in time to the birth of rationality. Rational thinking became more prominent after the philosophy of Socrates become popular.

Socrates questioned the beliefs of the people that lived during the time, and made people recognize that many of their long held beliefs were irrational and did not make much sense when scrutinized. By questioning the people through Socratic dialogue i.e. having them critically think about their own beliefs, rather than preaching to them, he made them evaluate their beliefs.

He asked them questions that they should have asked themselves, and made them realize that they were holding on to many beliefs that they did not fully agree with. Socrates made it clear that many people simply believed in things because they have always believed in them, and not because it made rational sense.

I think they find an abundance of men who believe they have some knowledge but know little or nothing. The result is that those whom they question are angry, not with themselves but with me. They say: “That man Socrates is a pestilential fellow who corrupts the young.” If one asks them what he does and what he teaches to corrupt them, they are silent, as they do not know, but, so as not to appear at a loss, they mention those accusations that are available against all philosophers, about “things in the sky and things below the earth,” about “not believing in the gods” and “making the worse the stronger argument;” they would not want to tell the truth, I’m sure, that they have been proved to lay claim to knowledge when they know nothing.

~ Socrates (The Apology by Plato)

People cannot lie to themselves, and so when faced with the contradictions in their beliefs while conversing with Socrates, they struggled (which is better known now as cognitive dissonance). Socrates was charged with the crime of “corrupting the youth” and for “impiety”, and was sentenced to death. Socrates taught us all about the importance of rationality, and how it can be a useful tool against irrational beliefs of the masses. The philosophy of Socrates was spread through the writings of Plato (his student), and gave birth to a new era of philosophy, and eventually to science itself.

Here there was a fork in the road. Science separated itself from philosophy and became its own thing, but the field of philosophy continued to be explored. Most of what happened later in philosophy was a chain of responses to ancient philosophers.

What Gave Birth to Rationality?

Just like how it works in science, philosophy continually renews itself, but unlike science, it does not base this off material evidence alone, but also through a deeper level analysis of the initial assumptions made by the older philosophers.

Think of science as a burrowing outward using rational thinking, and philosophy as the burrowing inward into the assumptions of thinking itself. Even though we are placing more emphasis on philosophy as it differs from science for the sake of this article, in reality philosophy is concerned with just about everything.

René Descartes in his A Discourse on Method shared his thoughts on the subject:

I supposed that all the objects (presentations) that had ever entered into my mind when awake, had in them no more truth than the illusions of my dreams. But immediately upon this I observed that, whilst I thus wished to think that all was false, it was absolutely necessary that I, who thus thought, should be somewhat; and as I observed that this truth, I think, therefore I am (COGITO ERGO SUM).

Descartes believed through rational thinking (i.e. the foundation of everything scientific) that he could only be certain of one thing which is that he exists. Everything else could be an illusion.

Friedrich Nietzsche is one of the greatest philosophical minds of the late 19th century and responded to this claim in his book Beyond Good and Evil (Aphorism 17) as such:

I shall never tire of emphasizing a small terse fact, which these superstitious minds hate to concede — namely, that a thought comes when “it” wishes, and not when ‘I” wish, so that it is a falsification of the facts of the case to say that the subject “I” is the condition of the predicate “think.” It thinks; but that this “it” is precisely the famous old “ego” is, to put it mildly, only a supposition, an assertion, and assuredly not an “immediate certainty.”

After all, one has even gone too far with this “it thinks” — even the “it’ contains an interpretation of the process, and does not belong to the process itself.

It was pretty much according to the same schema that the older atomism sought, besides the operating “power,” that lump of matter in which it resides and out of which it operates-the atom. More rigorous minds, however, learned at last to get along without this “earth-residuum,” and perhaps some day we shall accustom ourselves, including the logicians, to get along without the little “it” (which is all that is left of the honest little old ego).

Nietzsche in the excerpt above says how there is no “I” behind the thinking, because that is just our ego talking, and how we are simply responding with our instincts i.e. our drives, which is better referred to as “it”.

Nietzsche further explains how even the “it” is also an interpretation of the process, and maybe one day we ought to do without “it” entirely.

He further dissects into Socrates with the following (Aphorism 191):

Socrates had initially sided with reason; and in fact, what did he do his life long but laugh at the awkward incapacity of noble Athenians who, like all noble men, were men of instinct and never could give sufficient information about the reasons for their actions? In the end, however, privately and secretly, he laughed at himself, too: in himself he found, before his subtle conscience and self-examination, the same difficulty and incapacity. But is that any reason, he encouraged himself, for giving up the instincts? One has to see to it that they as well as reason receive their due-one must follow the instincts but persuade reason to assist them with good reasons. This was the real falseness of that great ironic, so rich in secrets; he got his conscience to be satisfied with a kind of self-trickery: at bottom, he had seen through the irrational element in moral judgments.

He states how the people were unable to give a rational answer to Socrates because they were men driven by instincts, and even though Socrates stunned them with his questions, Socrates himself was unable to do any better than them, because all our actions stem from our instincts.

We rationalize our instincts, which are otherwise irrational by default. In other words, the rationalization accompanies and assists with the action, but does not cause the action.

What does Science say about this?

So is this just a hypothetical or is this actually what happens? Thankfully advances in science made it possible to verify this part of the discussion:

The results suggest, in normal individuals, nonconscious biases guide behavior before conscious knowledge does. [source]

These findings support the conclusion that frontopolar cortex is part of a network of brain regions that shape conscious decisions long before they reach conscious awareness. [source]

We found that the outcome of a decision can be encoded in brain activity of prefrontal and parietal cortex up to 10 s before it enters awareness. [source]

overwhelming evidence from neurosciences demonstrates that our actions are instead largely driven by brain processes that unfold outside of our consciousness. [source]

Delving into the Depths

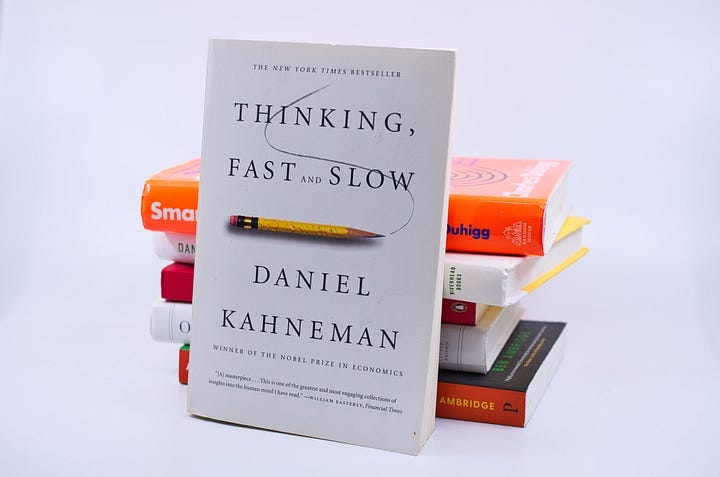

Another good source to learn more about this is in the book Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahnman. However, the author of the book classifies the different types of thinking into two groups System 1 and System 2.

System 2 is what we consider ourselves i.e. our ego and our rational brain. System 1 is what is the irrational part of the brain.

The term “irrational” is not the correct term to refer to the other part of our brain, because its a negative term i.e. it signifies what it is not. It is better understood by us in terms of our drives, which includes our instincts (gut feeling) and emotions.

We don’t choose to be hungry, sleepy, thirsty, etc, but are driven to act based on those drives, and convince ourselves afterwards that we actively made the choice to do so. We are constantly trying to fulfill all the needs of our drives and afterwards, we interpret them as things we chose to do according to our free will.

Our drives are far more capable and far more powerful than our rational brain. Our rational brain is highly limited and plays a significantly minor role in our daily lives than what we would like ourselves to believe.

Daniel Kahnman’s book is filled with many examples and research to support these ideas. There is so much great information in the book for those who are unconvinced and need to take a deeper dive, but here are some good excerpts:

When we think of ourselves, we identify with System 2 [rational brain], the conscious, reasoning self that has beliefs, makes choices, and decides what to think about and what to do. Although System 2 believes itself to be where the action is, the automatic System 1 [our drives] is the hero of the book.

[…]

System 1 continuously generates suggestions for System 2: impressions, intuitions, intentions, and feelings. If endorsed by System 2, impressions and intuition turn into beliefs, and impulses turn into voluntary actions. When all goes smoothly, which is most of the time, System 2 adopts the suggestions of System 1 with little or no modification.

~ Daniel Kahnman, Thinking Fast and Slow

In other words, we are controlled by our irritational brain (our drives, instincts, and emotions) far more significantly than our rational brain. To create a positive change in this world, we have to be aware of these underlying drives that control us so that we can understand how to work with them to better drive ourselves forward.

And in doing so, we will be able to create lasting changes in a way that both brings meaning to our lives (by fulfilling the needs of our drives) and will put us in the best position to solve the problems of the future. However, if we attempt to only solve the world’s problems using our rational mind and disregard our drives, we will never manage to solve anything and we will fail to understand why.

The Inner Conflict

One of the best depictions of this concept is seen in the book Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. For those who haven’t read this book, the story follows an impoverished man, Raskolnikov, who rationalized the idea of murdering a pawnbroker, because he believed that the crime was justified as the world would be better off without her, and that he could then sell her valuables to get out of poverty and create a good life. However, once he had committed the act, he started losing his mind as he struggled with the guilt and the horrors stemming from the act.

In this story, Raskolnikov had rationalized the murder in his mind, but his drives i.e. System 1, did not actually agree with his actions unbeknownst to his rational brain (System 2). The end result is that he was tormented by his own mind once the act was committed, because he didn’t actually agree with his own actions.

This is a perfect example that shows how attempting to solve problems by only using our rational minds can be disastrous because if we do not understand our drives, then we will arrive at a solution that is likely to do more harm than good.

This concept of our drives vs the rational brain is also explained in psychology, using different terms. However in other areas of science, since science is constructed by the rational brain, there is an overemphasis of the rational mind and an underemphasis of the irrational mind i.e. our drives.

We can be blind to the obvious, and we are also blind to our blindness.

~ Daniel Kahnman, Thinking Fast and Slow

Sigmund Freud presents the same concept in terms of the ID, Ego, and the Superego. The ID represents our drives, the ego represents the rational brain, and the superego represents our ideals i.e. what we aim towards. We have already discussed ideals in-depth in another article here.

The ego is not master in its own house.

~ Sigmund Freud

However, at a later point in his life, Freud recategorizes the mind again more clearly into the conscious (rational mind) and the unconscious (our drives).

Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.

~ Carl Jung

Carl Jung is another psychologist that has also done considerable work in the field with regards to these concepts, but he also used slightly different words. He referred to the unconscious as the Shadow.

He also came up with some wonderful insights about the shadow (our drives). Some of which are shared below:

If you imagine someone who is brave enough to withdraw all his projections, then you get an individual who is conscious of a pretty thick shadow. Such a man has saddled himself with new problems and conflicts. He has become a serious problem to himself, as he is now unable to say that they do this or that, they are wrong, and they must be fought against… Such a man knows that whatever is wrong in the world is in himself, and if he only learns to deal with his own shadow he has done something real for the world. He has succeeded in shouldering at least an infinitesimal part of the gigantic, unsolved social problems of our day.

~ Carl JungWe carry our past with us, to wit, the primitive and inferior man with his desires and emotions, and it is only with an enormous effort that we can detach ourselves from this burden. If it comes to a neurosis, we invariably have to deal with a considerably intensified shadow. And if such a person wants to be cured it is necessary to find a way in which his conscious personality and his shadow can live together.

~ Carl Jung

The Birth of Propaganda and Public Relations

For those who are still unconvinced about the power of our drives and the hold that it has over our minds, we just have to look into “Father of Public Relations” i.e. Edward Bernays.

Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud, learned from his uncle’s findings, and applied these ideas to control people without their own knowledge. He used these ideas to promote smoking among women with his “Torches of Freedom” and later helped the CIA overthrow the Guatemalan government. But the manipulation of our drives is another topic altogether, and we won’t go into that for the purpose of this article.

Our Drives Give Us Our Meaning

Science studies what is known and testable, which means that it has to be repeatable by anyone anywhere. However, these are the rules of science, and not the rules of life itself. We have to remember that science is supposed to be a tool to understand life, and the limitations of science, do not restrict the possibilities in life.

We fundamentally do understand this concept with our “irrational” brain, even though we might not fully rationally realize it. Some of the best moments of life are unplanned and unorchestrated. This is because the feelings brought about by experiencing things first hand and for the first time, are unreplicable. Some experiences also cannot be put into words, like how it feels to be a parent for the first time and holding your own baby in your arms for the first time. The more you try to replicate it to study it, it reduces the feeling drastically. Even by putting the experience into words, you have reduced it.

Our rational brains like to control and understand things, but these things are out of grasp of the rational brain. For instance, if you tried to replicate some of the greatest moments of your life that you had with your friends or family, it will always fall short and likely be completely forgettable — unless there are moments that make it unique and particularly amazing on its own.

This is because the feeling of the unknown unraveling as you experience it, is not reproducible. The subjective feeling of experiencing life i.e. qualia, cannot be described. The more you try to learn it, the less emotionally exciting it becomes. Often times, people can feel frustrated about how their partners or loved ones cannot not fully understand how they feel during an emotionally charged moment in their life; this is because the experience of being you is unique and even though others can understand it when you describe it, it will always be a lesser form of what you actually experienced.

The more you rationally understand something, the less you actually experience it. Mark Twain beautifully expresses this same idea in his essay Two Ways of Viewing the River.

We also understand this concept in psychology to a certain extent. The more you are used to the same stimulus, the less response it produces. The more unique the stimulus, the more stronger the response.

The other interesting aspect of this is that the unknown not only produces inexpressible feelings within yourself, but also bring about unknown parts of your own being. You can reveal yourself in new and unexpected ways when you are put in unique situations, which will even surprise yourself. This is also not reproducible because you can only surprise yourself with the same thing once. For example, when you finally successfully learn how to ride a bicycle for the first time — you surprise yourself by showing that you have what it takes to perform the task, and that feeling and experience with the bicycle cannot again be replicated.

In each of us there is another whom we do not know.

~ Carl Jung

The most beautiful moments in life are the unique and experienced within yourself, and by its very nature — not expressible completely in words.

Friedrich Nietzsche had great insights about human nature, and has expressed these same ideas here:

Owing to the nature of animal consciousness, the world of which we can become conscious is only a surface and sign-world, a world that is made common and meaner; whatever becomes conscious becomes by the same token shallow, thin, relatively stupid, general, sign, herd signal; all becoming conscious involves a great and thorough corruption, falsification, reduction to superficialities, and generalization. Ultimately, the growth of consciousness becomes a danger.

~ Friedrich Nietzsche (GS 354)

What does this mean for us?

Our drives are something that has evolved over a long period of time starting from the beginning of life itself (ex. drive to multiple, drive to hunger, drive to survive, etc) and that is why they are far more capable than the rational mind, which has more of a recent history of coming into existence with the birth of consciousness and through philosophical thinking as explained earlier. Oftentimes in scientific literature, the irrational part of our brain i.e. our drives have been considered incorrectly as the “inferior” or “lesser” part of the brain, because it is primitive and because it is not rational, but nothing could be further from the truth.

By understanding ourselves, we can begin to understand why we behave in a certain manner, and more importantly, what it would take to make mankind change its route to a preferable path that doesn’t end up in self-destruction. However, this requires us to see ourselves through the lens of our instincts, emotions, and feelings that has evolved through time, and for as long as we are stubbornly refusing to embrace our “irrational side” and are waiting for things to make rational sense, we will fail to fully understand our own existence and the way forward.

Right on. I fear you may find it difficult to get through to most people with this message, I know I have. Rationality, and its brother objectivity, give people a sense of comfort, and are socially enforced. But as Nietzsche saw, rationality is a suppression of instincts in response to the mandates of society. I like this line in Beyond Good and Evil where he seems to be talking about rationality:

"The will to overcome an emotion, is ultimately only the will of another, or of several other, emotions."

I'd even argue that what you've written doesn't go far enough. I'm looking at this from the perspective of AI, and AI has always had as its model the "rational agent". This, I believe, has severely hindered its creative capabilities and ability to generalize. I wrote about formal logic in AI in this series (https://ykulbashian.medium.com/the-green-swan-6d1bc569684f). Here's a quote from that series I think is applicable:

"Motivated, non-logical thinking is your default way of addressing the world. Out of these roots formal logic grows like a well-pruned branch. Formal logic is just a flavour or type of motivated thinking, one that tries to conform language and symbols to a communally agreed upon set of rules."

Looking forward to reading more from you.